|

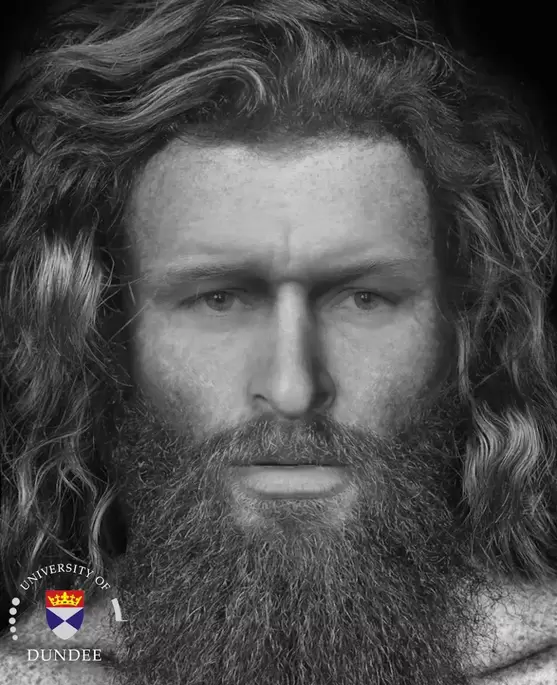

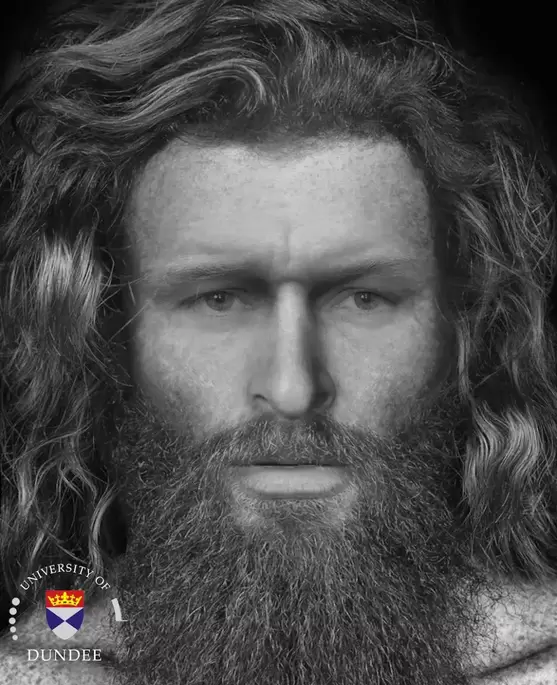

image credit: Christopher Rynn, University of Dundee Happy Medieval Monday!

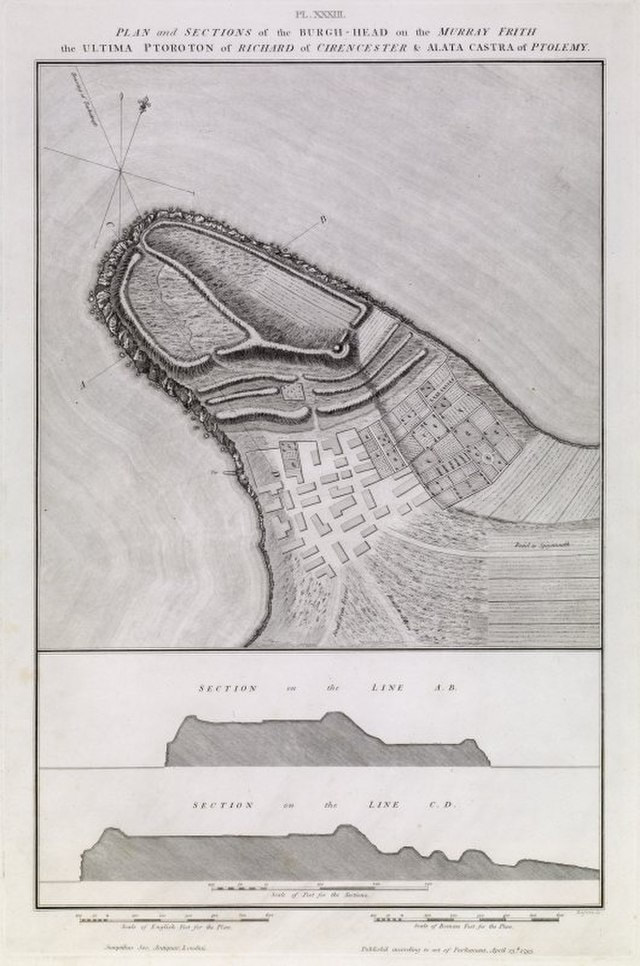

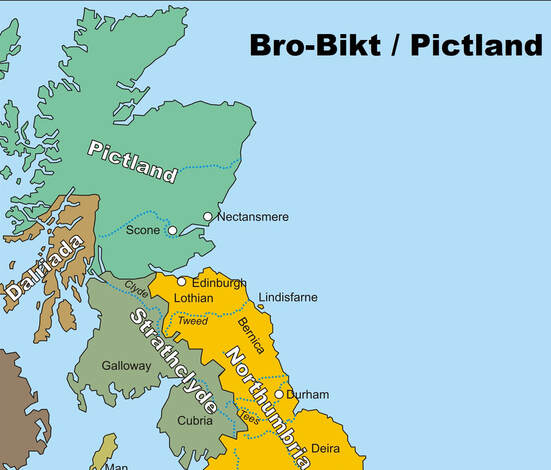

In 2017, Professor Susan Black of the University of Dundee, Scotland, was on an archaeological dig on Black Isle, Ross-shire, Scotland with Dr. Christopher Rynn and three PhD students when they discovered the remains of a man buried in a cave. According to Professor Black, he had been brutally beaten to death, but buried carefully, laid in an unusual position, and in a protected location in the back of the cave. Despite his battered skull, researchers at the University of Dundee were able to reconstruct his face using digital imaging. To me, the man looks strikingly modern. Why do I feel a bit surprised? What else should I expect of anyone without worldly trappings affecting their appearance? It's so easy to dehumanize others -- whether in the past or, worse, even in the present. He might have been a bad guy. He might have been cruel. He might have been a great leader, betrayed. We will probably never who he was. But from now on, when I think of the Picts, his face will come to mind. There've been a lot of archaeological discoveries all over Scotland the past few centuries. One very impressive site is the hillfort at Burghead. Radiocarbon dating shows that the fort's construction began as early as the 3rd century, and it's presumed to have flourished between the 4th and 9th centuries. Over 12 acres, it's the largest pictish settlement ever discovered and surely a main center of power for the Picts. Findings at the site show it was a center of both commerce and religion. I owe it to the Picts to write at least one more post about them -- about their writings, their art, their body-paint. But it will be a few weeks. I'll be away and mostly offline for a little while. I can hardly wait to tell you all about it! Be sure to visit the marvelous, medieval ladies Mary Morgan and Barbara Bettis! Wishing you a happy, wonderfully medieval Monday!

6 Comments

"The True Picture of a Woman Picte", engraving by Theodor de Brys, 1588 Happy Medieval Monday! It's been a fascinating time, learning, un-learning, and repeating the process several times over as I've made the acquaintance of the ancient people called the Picts. I have to say, I absolutely love them. No one seems to have a really firm grasp as to who they were, where they were from, or how their language sounded. Possibly the biggest mystery of all -- since they were a known people during recorded history -- is what happened to them? It would seem that someone should know something. Right? Yes, I'm a bit cranky about it. To be fair, it's only because the Picts didn't leave a lot for us to work with -- at least, not a lot has been uncovered yet. But archaeologists continue to make amazing discoveries. They lived in northern and eastern Scotland. Growing evidence shows they were there in the Iron Age which, in Britain, was from roughly 750 BC to when the Romans invaded in the first century AD. It's hard to even know which question to address first! I've decided to go with their name. After all, that is usually first in order when getting to know someone. Then, since it sort of ties in, I will add a few words about where they came from. It's worth pointing out that no one is even sure what they called themselves. I've found a few resources that suggest they might have referred to themselves as the albidosi, as in of the Kingdom of Alba (Scotland). I like that. So where does the name "pict" come in? The most popular theory is that the Romans gave them the name. “Pict” or “Picti” in Latin means “painted people”. It is assumed that this would have been the Romans' way of painting them (no pun intended, but HA) as savages, referring to their blue war paint. But there’s another theory out there that I personally prefer -- that "pict" might be a word of proto-Celtic origin. Cruithni (Irish), prydyn (Welsh), and pretani all mean "ancestors". It's been suggested that pict or pecht (Scottish Gaelic) comes from these old, indigenous words. Ancestors. That brings me to where they came from. Some sources suggest that they came from Scythia. Others, from Ireland. These are the most popular theories, but not the only ones. There's one theory gaining steam that I personally feel is the obvious right choice. Of course, all the work has been done for me. Moreover, what do I know? I'm just getting to know these folks. But I appreciate the suggestion that the picts were indigenous to the land -- indigenous to what is now Scotland. To me, that makes the most sense. Ancestors. Right. To say nothing of Iron Age evidence... I'm going with it. But that's just me. Before I go, I thought to share this astonishing, digital image (University of Dundee) created from the well-preserved remains of a Pictish man. He was handsome and died a violent death. I'll tell you more about him next week. For more medieval fun, be sure to visit these medieval ladies, Barbara Bettis and Mary Morgan. Wishing you a great week ahead! The digitally recreated face of the Pictish man. (Image credit: Christopher Rynn/University of Dundee)

tapestry of King Arthur that hangs in The Cloisters, New York c. 1385 author unknown Nope! King Arthur was not a bard. At least, not to the best of my knowledge. But we know of him because of bards. Their oral traditions kept his legend alive until that time when they were written down. And so it was with all the lore and history handed down by word of mouth for generations upon generations before writing. Happy Medieval Monday! When I began researching this topic -- bards -- I realized it might be vast. But I had not an inkling... The term “bard” comes from the Proto-Celtic word bardos, which referenced a poet-singer or minstrel. But bards were known by other names in other places, and they were not all singers or musicians. While their responsibilities obviously varied from place to place and in different times, their responsibilities were multifold, serious, and often took courage. They were the ones who made the rounds and shared good news and bad with their king/patron/chief as well as the people. They went into battle with their lords to both provide stress relief for the warriors and to witness their deeds. They were storytellers of the highest degree, teachers, historians, and genealogists. So much from religion and prehistory would have been lost without the bards. The Scottish bárds passed down clan history. In Ireland, there were different classes of bards. There were also Druid bards who were honor-bound to keep Druid lore alive but secret. Welsh bardds kept King Arthur’s legends alive. French troubadours romanticized it. Norse skalds told the sagas. To say nothing of the world of religious traditions, creation stories, and ancient myths, etc., etc. It gladdens my heart to know that there is a resurgence in the bardic tradition. Many, many storytellers honor their mission and take it seriously. Bards are not prophets. They’re more historians. Aren’t they? In viewing time as more fluid -- ebbing and flowing -- perhaps they’re both? Be sure to visit Barbara Bettis and Mary's Tavern for more Medieval Monday! Now available at all major online bookstores.

So much delicious romance, so little time! Happy Medieval Monday! The Medieval era was long and varied -- from approximately 500 CE to 1500. Although popular fiction might have us believe otherwise, it does refer to the whole world, not just Europe. I point this out because there was a lot more travel than we generally consider. Vikings were all over the place, as were missionaries, explorers, merchants, and pirates. To write a solid historical novel, a writer has to do a surprising amount of research. One thing leads to the next and the next... There is a lot of fiction written by PhDs and I can understand why. History is fascinating and demands to be remembered and shared. In my opinion, medieval history calls to be revealed in all of its richness and glory and gore. They don't all have to be in one story. Personally, I do very well without the gore. That's just me, of course. I love the beauty and mystery of it all. There are so many wonderful writers who craft magnificent, medieval tales of adventure and romance. Some amazing authors -- just to get you started: Mary Morgan, Barbara Bettis, Judith Sterling, Ruth A. Casie, Mary Gillgannon, Amy Jarecki, Sherry Ewing, Cathy and DD MacRae, Jenna Jaxon, Sophia Nye, Madeline Martin, Eliza Knight, Tanya Anne Crosby, Julie Garwood, Vonda Sinclair, Shelly Thacker, Mairi Norris, Ashley York, and a new favorite, Virginie Marconato. Some write in a variety of romance subgenres and some write strictly medieval romance. Some add fantasy to the history, some do not. They all write beautifully. Care to disappear for a while into a world of magic and mystery, chivalry and romance? Try one of these authors. Oh, and you might want to check out my time travel romance, Tremors Through Time. :) Be sure to visit Mary Morgan and Barbara Bettis (beloved authors of mine) for more medieval romance! Available at your favorite online bookseller.

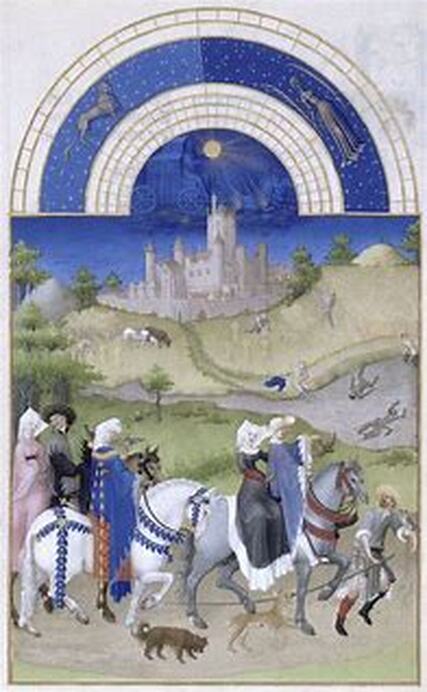

August, Limbourg Brothers, Les Très Riches Heures Happy August, Happy Medieval Monday! Hard as it is for me to imagine here in the heat of a Texas summer, the first of August marks the beginning of harvest time in many countries. For ancient Gaels, August 1 meant the festival, Lughnasadh/Lughnasa. Those are the ancient words. Called Lùnasta in modern Irish and Lùnastal in Scottish Gaelic, it's one of the four seasonal Gaelic celebrations (along with Samhain), Imbolc, and Beltane). It was in celebration of the beginning of the harvest season. In Tremors Through Time, it was this festival which took Lachlann away from his family for a short time, only to return to devastation. Scottish Highlands, 1351 Shrouded in mist, Loch Nis loomed, dark and foreboding, in the distance. Lachlann pulled the packhorse along swiftly, anxious to be home before nightfall. He needed to see his family, to hold his son. He checked his sporan. The wee leather ball and wooden horse figurine were there, safe. He could hardly wait to watch Iain’s little face light up when he gave him the toys. Allasan should be pleased that he’d found everything on her list. He grinned. They had their differences, but if there was one thing about his wife, she knew what she wanted. She was the most stubborn Gael alive. Despite fever, nausea, and a sick three-year-old to care for, she’d almost pushed him out of the door. You have to go,” she’d urged, her brown eyes unnaturally bright. “I want the dye and you’ll find it in Inbhir Nis. You promised! I didn’t work day and night all summer to be disappointed because of a paltry ailment. I have my family and yours all around me if I need anything. Go! You’ll only be in my way here!” He had to admit, she’d been right. The Lùnastal festival in Inbhir Nis was much larger than their local fairs, with a wider variety of merchants in attendance. Not only had he found her purple dye and wax candles, but all sorts of vegetable seeds as well, even Norse Anastasia Abboud 8 favorites such as horseradish and mustard. Thanks to a bountiful harvest and the cloth that Allasan wove so skillfully, he’d had plenty with which to barter. He’d even been able to choose gifts—Iain’s toys, silk ribbons for his wife and sisters-in-law, and iron gall ink for the bard. He only wished that Allasan and Iain had been able to go with him as planned. He’d worried about them the whole week. What’s wrong with the horse? He tugged lightly on the rope. The beast stalled, its ears flat back. He tugged harder, then smelled it, the foul stench of smoke Available in ebook and paperback from your favorite online bookstore.

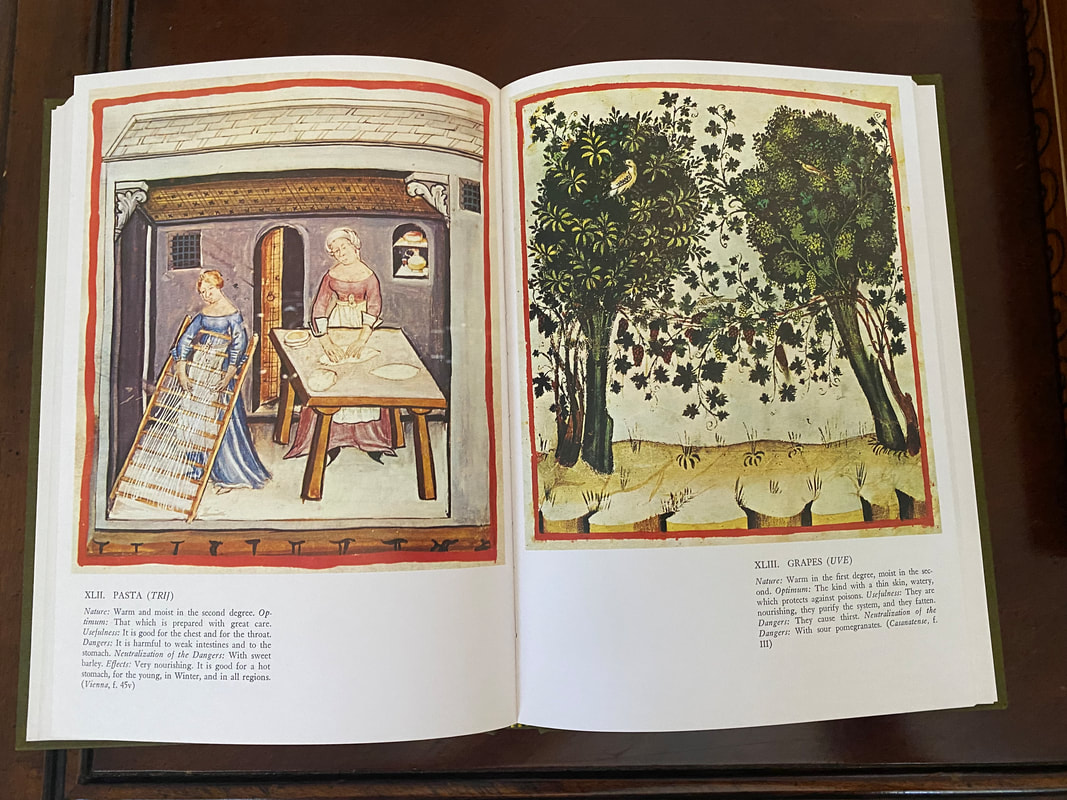

Wishing you a wonderful beginning to both the new week and new month! XLII. PASTA (TRIJ) Nature: Warm and moist in second degree. Optimum: That which is prepared with great care. Usefulness: It is good for the chest and for the throat. Dangers: It is harmful to weak intestines and to the stomach. Neutralization of the Dangers: With sweet barley. Effects: Very nourishing. It is good for hot stomach, for the young, in Winter, and in all regions. (Vienna, f. 45v) Do you love pasta? I'd like to dedicate today's Medieval Monday post to our grandchildren, Colette and Oliver, who are vacationing with their parents in Italy right now. Like their beautiful mommy Julia, they are pasta-lovers. I'm sharing this color plate from the Vienna Tacuinum because along with its notation, it made me smile. It seems that like all foods, even pasta should be prepared with loving care for optimum nourishment. I would not have guessed that it's good for chest and throat, but for Julia's and the babies' sakes, I'll accept. But barley? Could it possibly reduce that full feeling after enjoying a healthy portion of one's favorite pasta? Has anyone tried it lately? In any case, the particular medieval physician clearly believed in his carbs! In my handbook's collection, grapes are showcased on the facing page. A wonderfully Italian display, don't you agree? It doesn't have to be in a health manual to know that a little fun and relaxation is good for you -- but there it is! So why not enjoy a little pasta, some vino, and la dolce vita?

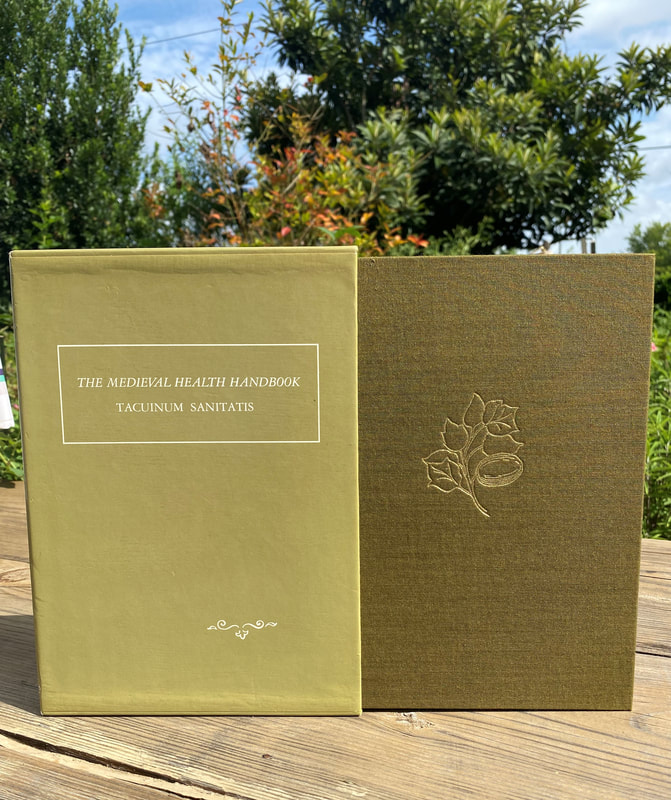

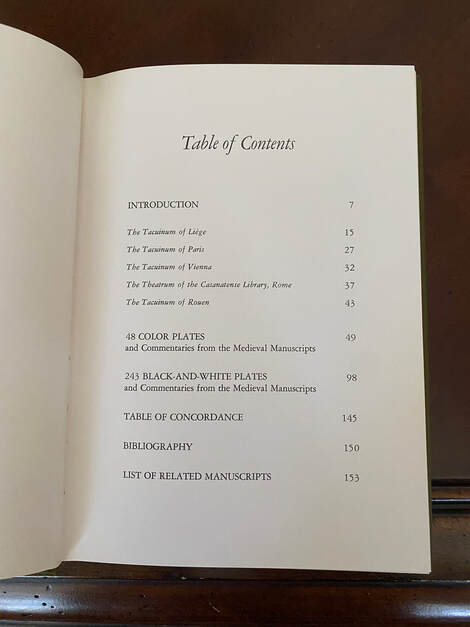

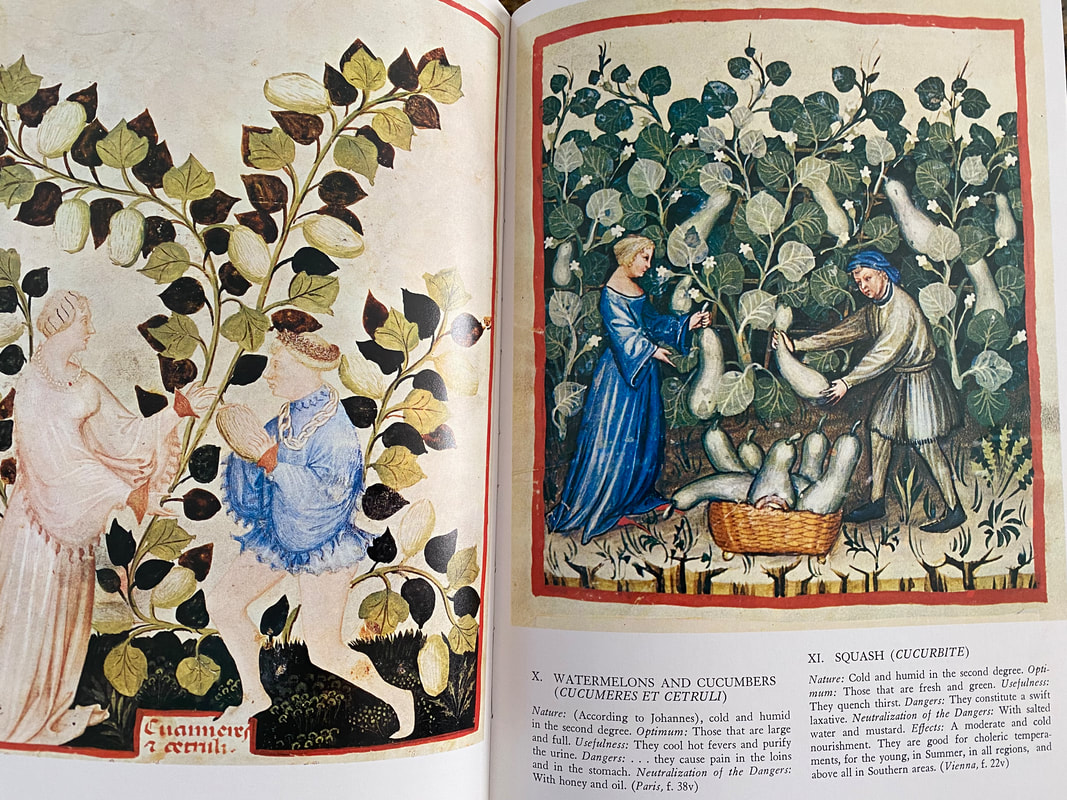

Salute! Happy Medieval Monday! Obsessing on my garden these days and I thought to share a little of this little handbook that I love. I'm so proud of it that anyone might be surprised it's not an original edition! It's just that it's the sort of health handbook I appreciate, all about herbs and human temperament and natural elements. And the illustrations are beautiful! Tacuinam Sanitatis was first published in Italy in 1976. Author Luisa Cogliati Arano chose colored plates from several different medieval manuscripts. Those manuscripts, in turn, had been translated into Latin from Ibn Butlan's eleventh century handbook Taqwim al-Sihhaa. Isn't that amazing? My version of the handbook is in English. It was translated in 1976 by Oscar Ratti and Adele Westbrook and published in New York. While I would love to know Italian, I am grateful for this translation. The Physican Speaks: The Tacuinum Sanitatis is about the six things that are necessary for every man in the daily preservation of his health, about their correct uses and their effects. The first is the treatment of air, which concerns the heart. The second is the right use of foods and drinks. The third is the correct use of movement and rest. The fourth is the problem of prohibition of the body from sleep, or excessive wakefulness. The fifth is the correct use of elimination and retention of humors. The sixth is the regulating of the person by moderating joy, anger, fear, and distress. The secret of the preservation of health, in fact, will be in the proper balance of the elements, since it is the disturbance of this balance that causes the illnesses which the glorious and most exalted God permits. --Rouen, f. 1 The medieval illustrations/illuminations are accompanied by recommendations. For example, according to the The Taquinum of Paris, watermelon and cucumbers "cool hot fevers and purify the urine", but they might also "cause pain in the loins and stomach."

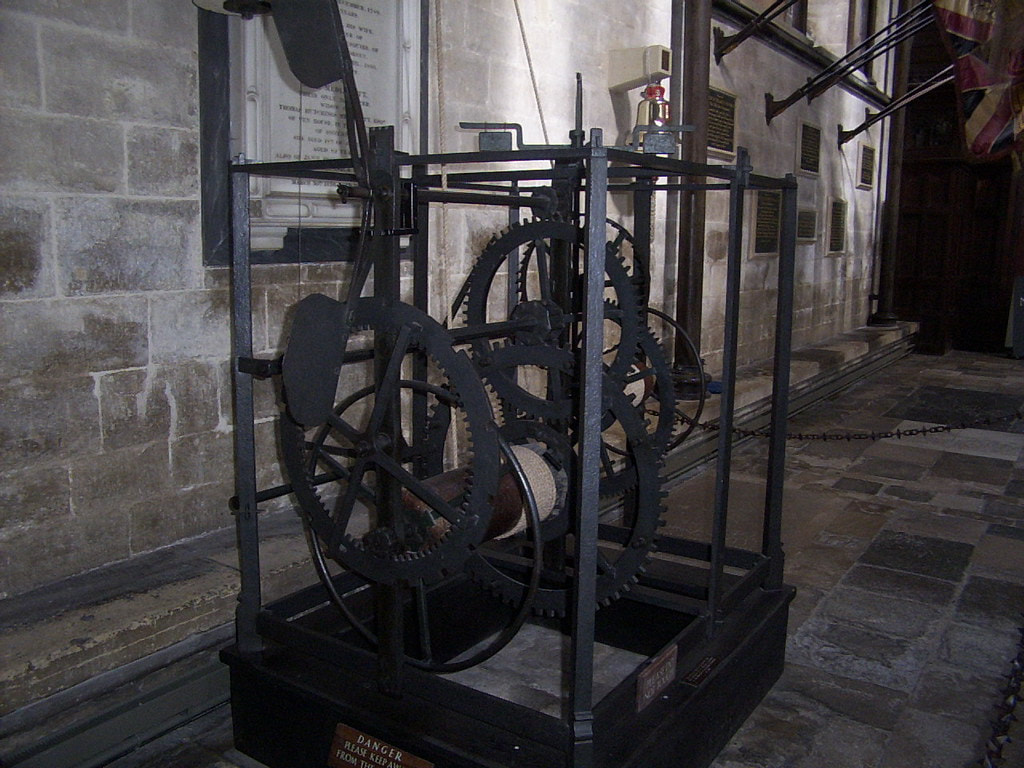

There's also advice as to how to minimize the danger, "with honey and oil". I'm not sure if that means to ingest honey and oil along with the cucurbits or only if they cause discomfort. But I have a feeling it would work. I'll share more about the book next week. After all, while my hero Lachlann probably would not have been aware of its existence, his contemporaries in medieval Scotland might have shared some of the same lore. Don't miss great posts from these magnificent medieval ladies! Medieval Monday: "BY THE SAINTS"-FASCINATING FEAST DAYS - Barbara Bettis - Historical Romance Author Medieval Monday | A Shift in Realms on a Journey to the Orkney Islands (marymorganauthor.com) Wishing you a wonderful week ahead! Happy Medieval Monday! I always have a wonderful time exploring the Middle Ages. Recently, I've become fascinated by some of the inventions. Continuing with last week's "timely" theme, did you know that the mechanical clock was a medieval invention? That surprised me. I'm not sure when I thought it had been invented, but certainly not as far back as the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century. As I've mentioned before, when I think of the medieval era, I tend to think of an agrarian society, not an urban one. For the medieval farmer, the sun moving from dawn to dusk was sufficient for calculating time. Certainly, in Tremors Through Time, it was all Lachlann needed during his medieval work day. The sun hung midway between heaven and earth, the great loch silver beneath it, as Lachlann An Damh plowed his field. But life in the cities ran on an altogether different schedule. So, too, did the monasteries that were popping up all over Europe. Monastic life centered around the Divine Office or Liturgy of the Hours. Moreover, wasting time was frowned upon. Knowing the exact time or hour became increasingly important. Churches and monasteries began developing and installing clocks. As church bells rang, merchants took note. Setting regular business hours suited them, too, as well as the variety of other establishments and venues found in urban areas. The mechanical clock (gears, weights, and pulleys) was not the first clock used to tell time. Since ancient times, sundials, obelisks, water clocks, hour glasses, and a variety of other ingenious methods had been used. But while surely better than nothing, they were not as dependable as the mechanical clock would be. The mechanical clocks were well-made. One of the oldest -- arguably, the oldest -- mechanical clocks in the world that still works is in Salisbury Cathedral, It was built around 1382 and originally placed in the cathedral's bell tower. When that tower was demolished, the clock was moved to the Cathedral, then eventually set aside to be replaced. It was rediscovered in 1928, ultimately restored, and now on display. These clocks changed the way time was ordered and therefore, often to no small degree, the way people lived. They remain one of the most impressive inventions of medieval times.

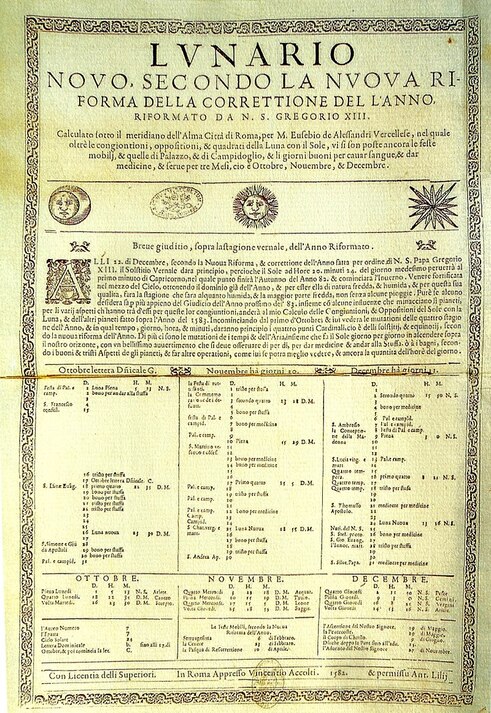

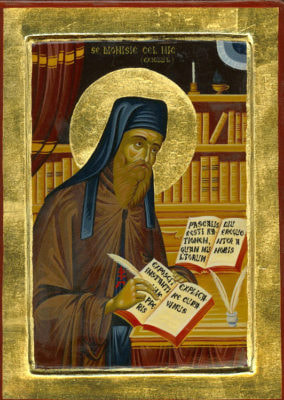

Personally, I still favor the sun-up, sundown approach. But that's mostly because I detest alarm clocks. For more medieval fun, be sure to visit these medieval ladies' websites: Mary Morgan Barbara Bettis For a delightfully medieval man, be sure to check out Tremors Through Time. It's set to launch July 6 and available for pre-order now. The Summer Solstice is upon us! The longest day of the year begins tomorrow, June 21, at 5:14 a.m. Then, in almost infinitesimal increments, nights will begin to lengthen as the summertime moves toward autumn. In the Middle Ages, long before climate control and GMOs, the summer solstice, often referred to as Midsummer, marked the halfway point to harvest time. Lachlann, our hero in Tremors Through Time, would have cared about that in his medieval days. But I don't believe he would have been terribly concerned about what year it was. He was too busy living his life to count the years. And then time does a trick on him... How important is time and the counting of it? Except for documentation, does what year it is really matter? I suppose it would depend upon whom you ask. Julius Caesar...some ego, right? He would decide that time should be considered to have begun at the beginning of his reign. Henceforth, at least to the Romans (whose dominion was far and wide), the counting of years was based on the consulship. For example, "this is the second year of so and so's rule". It didn't take long for it to become obvious that that method wouldn't work forever. The Julian calendar had other problems, too -- major issues with leap years and the Easter tables. That last thing, the Easter tables, was a subject worthy of an 800-page volume of work, amongst many other documents. My simple summary is "how to set the date for Easter". It took an early medieval man to get things under control. The dating of Easter was a serious concern and cause of contention for the Church. Pope John I requested a monk to look into the matter, but not just any monk. Dionysis Exiguus (Latin - Dionysis the Humble) was highly respected for his brilliant scholarship. He set about righting the Easter tables. He also invented a system -- the system -- of numbering years from the Incarnation of Christ. At the time, from all his gathered resources, he calculated that 525 years had passed. He referred to the system as Anno Domini, the Year of the Lord. In other words, he approximated that it was the year 525 A.D. His system was incorporated into the Julian calendar. Nowadays, the more commonly used terms might be CE -- for Common Era -- and BCE -- Before the Common Era -- but the years are still based upon Dionysus Exiguus' calculations. But the calendar still had problems. By the 1500s (over a thousand years later), it was so misaligned with the solar calendar that the (northern) spring equinox was occurring long before its expected date in March, which again threw off Easter dates. It took another medieval man -- actually more than one -- in the High Middle Ages to right the fiasco. Pope Gregory XIII wanted the Easter issue resolved. Aloysius Lilius, an Italian astronomer, and Christopher Clavius, a German mathematician, were the primary architects of what came to be known as the Gregorian calendar. The auspicious day of the new calendar was October 15, 1582. One of the first printed editions of the new calendar, printed in Rome by Vincenzo Accolti in 1582. The Gregorian calendar isn't universally accepted, although most countries have adopted it as at least their civil calendar. It's also not perfect. But it's been working well enough for over four hundred years thanks to some prolonged medieval finessing. For more medieval fun, be sure to visit the blogs of these marvelous medieval ladies, Mary Morgan and Barbara Bettis. Happy Medieval Monday! Happy Summer Solstice! Dionysis Exiguus (c. 470-c. 544) Pope Gregory XIII (1502-1585)

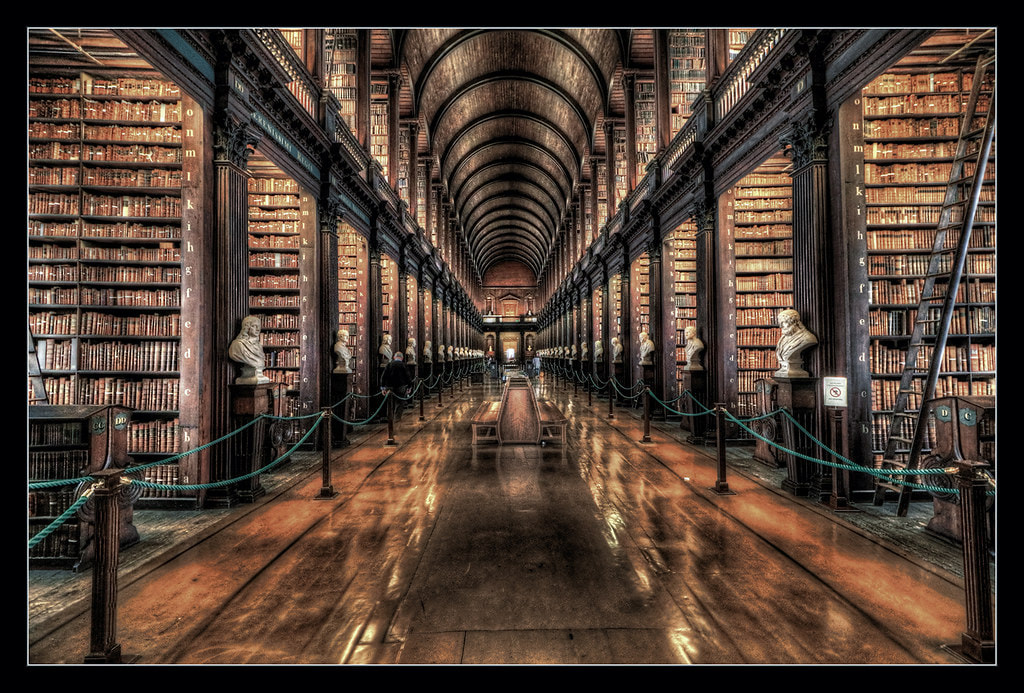

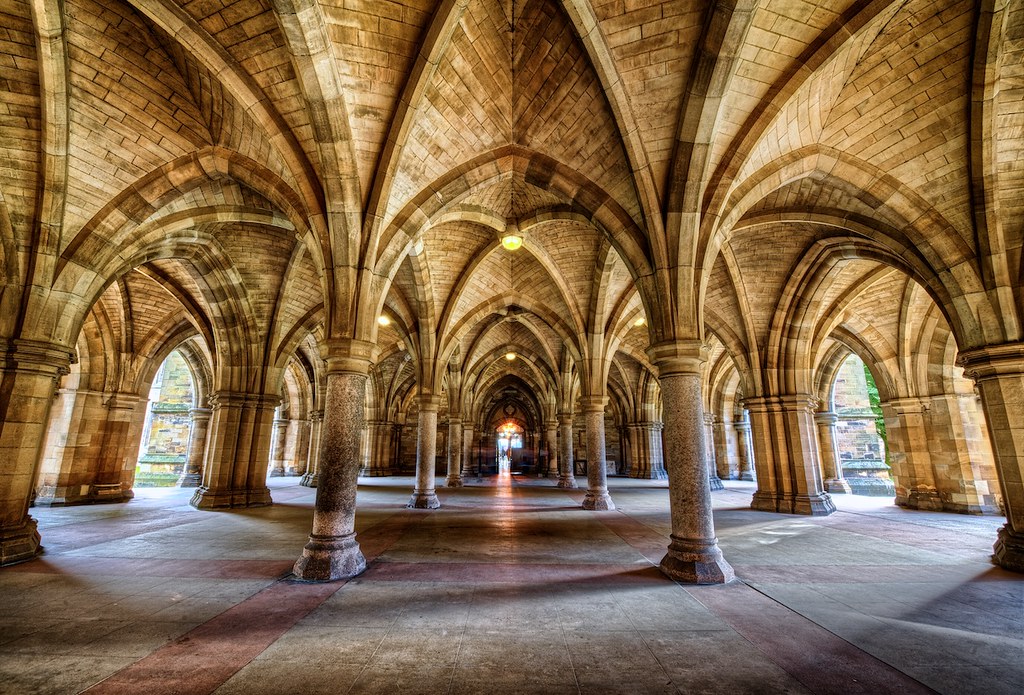

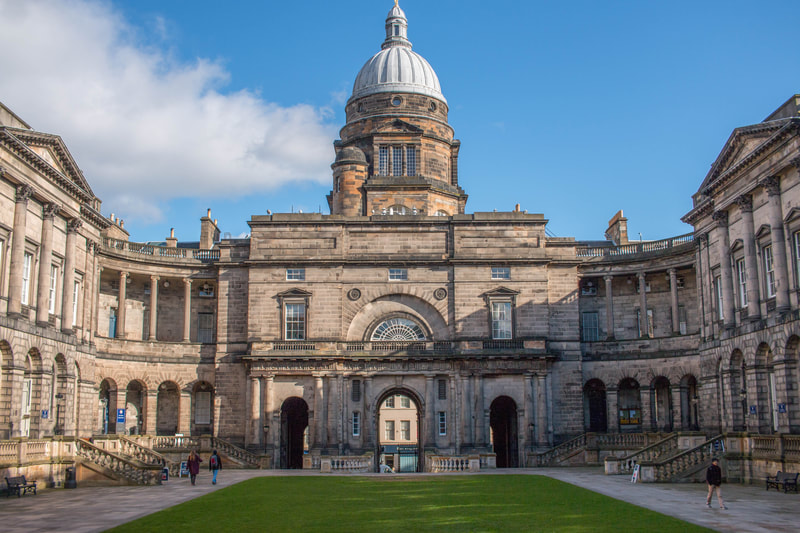

Dimitris Kamaris Archiginnasio, Bologna (26408793660).jpg via WikiCommons Happy Medieval Monday! Today, I am considering those institutions of higher learning known as universities. I have been amazed at how long some have been established. There are older university sites than the ones I am featuring. Al-Karaoine in Morocco and Al-Ahzar in Egypt are good examples. But while they have been universities for a very long time, they did not begin as such. For my purpose, I've chosen a not uncommon set of criteria -- that they have been continually in operation since inception and that they began as universities. Some of the universities were cathedral schools before they became universities -- all still way back when, others were royal charters, while even others were begun as student guilds. They were all established in the medieval era. It's awesome. The oldest is the University of Bologna, founded in 1088 by a guild of students. It's Latin name Alma Mater Studiorum means "Nourishing Mother of Studies". The students called it a "universitatis", first to do so, giving it a term from Roman law to designate a legal body. Oxford is the second oldest. According to the university, classes were taught as early as 1096. It was organized as a university between 1201 to 1214 and granted a royal charter in 1244. Its history is closely related to that of Cambridge University, which is third on the list. The University of Salamanca in Spain is fourth, founded in 1218. File:Old Library in University of Salamanca 01.jpg" by Antoine Taveneaux is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. There are many Italian universities that were founded during the medieval era. One of the older, non-Italian ones is the University of Coimbra in Portugal, It moved back and forth between Lisbon and Coimbra for a while, but was established in 1290. There are a few more I'd like to mention. Frankly, there are enough beautiful universities with long and fascinating histories to occupy countless blogposts. The Sorbonne was officially chartered in 1200 by Philip II and recognized fifteen years later by Pope Innocent III. It did not operate continually from its beginnings, however. The French Revolution sort of put it on hold. Thankfully, it returned. We cannot forget Trinity College in Dublin, home of the Book of Kells. "Dublin IR - The Long Room Of The Old Library At Trinity College 03" by Daniel Mennerich is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Scotland boasts some of the oldest universities in the English-speaking world. The earliest is the University of Saint Andrews (1410-1413), followed by the University of Glasgow (1451), and the University of Aberdeen (1495), and the University of Edinburgh (1582). From left to right: "University of St Andrews 4" by Son of Groucho is licensed under CC BY 2.0, "University of Glasgow architecture" by Jim_Nix is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, "University of Aberdeen" by readephotography is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0, "File:Old College, University of Edinburgh (24923171570).jpg" by LWYang from USA is licensed under CC BY 2.0. An astounding number of universities were established in medieval times that are still in existence and active. I find it uplifting to know that there have always been students who wanted to learn and teachers who wanted to teach. I believe it is a beautiful statement about humanity. In my time travel romance Tremors Through Time, Lachlann did not have the opportunity to attend a university. There were no universities open to him in the fourteenth century Scottish Highlands. However, he could have learned to read; he had a friend willing to teach him. He was too busy farming to consider it. Once he's stuck in this century, he wishes he'd taken the time to learn. For more Medieval Monday, be sure to stop by these beautiful blogs: Mary Morgan - Medieval Monday | A Love Affair with Medieval Romance (marymorganauthor.com) Barbara Bettis - Blog - Barbara Bettis - Historical Romance Author May we all continue to enjoy learning! Coming July 6! Available for Pre-order.

|

Romance!It's no secret that I prefer fat HEAs. Where better than in a beautiful romance? Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

NewsletterFrom me to you with a smile. Thank you!You have successfully joined our subscriber list. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed